Several years ago my mother wrote out a document, made copies and bound them in slim, dark-green, presentation folders for distribution to her children. They were recipes she wanted us to remember: charlotte russe with lady fingers, shortbread, quiche lorraine, stuffing and gravy, Grandmother Hill’s ginger cookies, biscuits, fried chicken, hominy grits, black-eyed peas for New Year’s Day, and pancakes (the secret of which is not so much in the recipe as in a particular, two-burner griddle with decades of memory cooked into the cast iron).

As you may have guessed, my mother is from the South—Augusta, Georgia to be precise. She moved north to New Jersey when she married my father. Along with those recipes, she brought with her a strong North Georgia accent, the first beautiful thing I ever heard. But Northern New Jersey had never heard anything like it. They say cocktail parties would fall into a brief lull at her first utterance. No conversation could proceed without someone asking, “Where are you from?” She found it exhausting always having to explain.

I think I know something of how she must’ve felt, having made my own long-distance move, and possessing of a conspicuous accent. The other day a crew of workers appeared with two jackhammers and back-hoe directly in front of our building. I went down, not to complain but to make a friendly inquiry about the purpose of the work and how long they were going to be at it. I said all of this in perfectly intelligible, correct Spanish, but with the accent (I now accept) I will never be able to shake. The foreman’s response to my questions was perfectly unhelpful: “De donde sos?” Where are you from? Really? Do we really have to chitchat about personal origins now, at 8:06 AM, here on the sidewalk, jackhammers a-blazin?

The question wasn’t meant to be aggressive or rude. He just couldn’t contain his curiosity. It happens a lot. Weehawken I said, though I’m not from Weehawken. I was just looking for the kind of place name that would illicit stupefaction and therefore bring his line of questioning to a close. It worked. There was no follow-up. They began excavating the sidewalk, leaving my accent intact.

It’s not the first time I’ve adopted that strategy, though the response I usually give is Lakehurst (the site of the Hindenburg Disaster, where I was in fact born). But this time it was Weehawken that popped out. I had visited a studio there in September. And it’s just a beautiful word to say. Weehawken. But then, Jersey is replete with beautiful place names, thanks to the Algonquin Lenapi people: Hoboken, Hackensack, Mahwah, Hohokus, Whippany, Munsee and Tammany. In any case it beats the hell out saying Estados Unidos.

My discomfort comes from being identified, pegged as an outsider, a gringo, yanqui or other. But honestly, is it really all that bad? It’s not something directed at me. I’m not being made the object of discrimination or violence. What I experience is not remotely comparable to how a Bolivian, African, or anyone living below the poverty line must feel as they negotiate the streets of this, our cushy neighborhood.

We come from where we come from. We end up somewhere else. My mother did, in ways that go far beyond geography. And so have I. We’ve both been changed greatly by our respective migrations. She’s been living in the North—or nawth, as she would say—for well over 60 years. And yet we both still (and always will) identify with where we began. Recipes, tastes, have a unique power to evoke a place, no matter how distant.

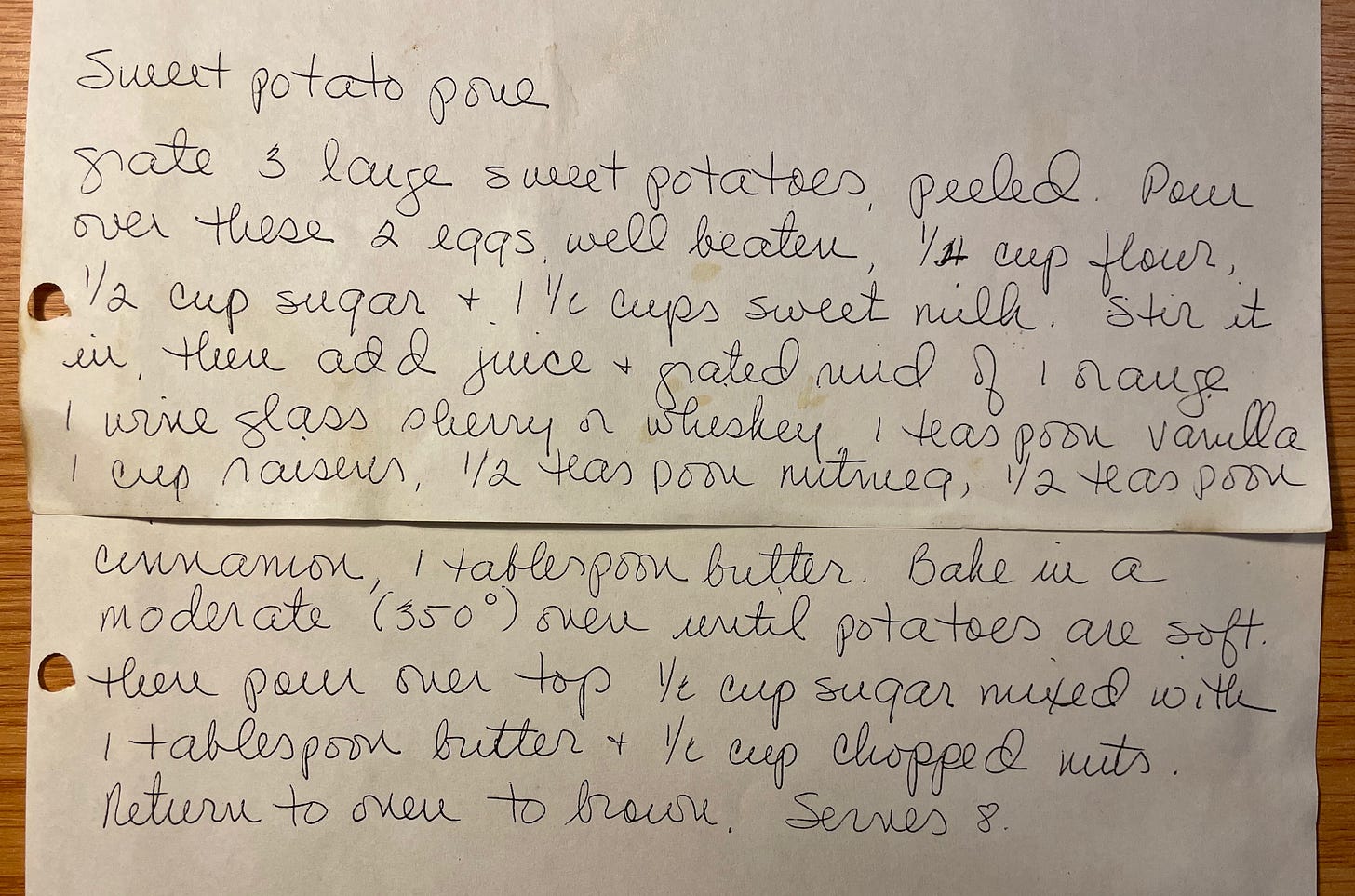

Take sweet potato pone for example. How far back it goes in our family is anyone’s guess. It is utterly delicious. The ingredients are common (sweet potatoes, orange juice, pecans, milk, eggs, butter, raisins, vanilla, nutmeg, cinnamon)1, but the taste is from another time, another world. In our family, no Thanksgiving or Christmas or Hannukah may proceed without it. Historically, it harkens back most immediately to my mother’s upbringing and previous generations going back to the Civil War—at least. Beyond that, sweet potato pone and dishes like it can be traced to slave communities in the late 18th century. Moreover, the words pecan and pone derive from the Algonquin. There are worlds in this recipe.

On a good day I can pronounce sweet potato pone in something approaching that Georgia accent. “Not bad, but not quite” Mom will say. But the words and their pronunciation—however beautiful to my ears, however significant to my biography—don’t come close to exhausting the resonance and significance of sweet potato pone. Let me know how it turns out.

Finally, here’s an instrumental version of “Christmas Time is Here”, by Vince Guaraldi. I’m playing electric guitar. Bob Telson is playing piano (the upright in my dining room). Enjoy.

For those of you asking about “sweet milk”, I consulted the oracle last night. She said sweet milk is just plain old milk (ie, as opposed to "sour milk"). But I recall her saying many years ago that it meant sweetened condensed milk. I think either will do. This dish isn't rocket science, and Lord knows it's already got enough sugar.

The question of origins and how to present mine is one that’s jumped to the front of my mind in recent years. Every time I open my mouth to someone who doesn’t know me in Ukraine, where I spend about a quarter of my time, anything I might say is secondary to the fact of it being in a British accent. The accent means: a friend’s here to help. For some people that’s mildly gratifying; right up to people crying and repeatedly thanking me because ‘You saved us.’ (Because we were one of the first countries to send Ukraine serious weaponry when others were just throwing up their hands.) And it varies between urban Kyiv and villages in de-occupied Kherson, obviously.

Given the historical penchant of Western Europeans in general and the British in particular for murdering everyone and nicking their stuff, and their justified objections to this, I found this positivity unnerving at first, but I think I’ve worked it out. It now goes something like this. Ukrainian: ‘You saved us! Thank you!’ Me: ‘Ukraine is the shield of Europe, protecting us from Putin! Thank you!’ And everyone’s day is a little brighter for the exchange. (Except when it devolves into a lengthy political rant that I’m unable to follow because it mixes the Ukrainian and russian languages apparently at random, but that’s another story.)

Of course, most reactions aren’t that extreme, but on one occasion I gave a begging grandma an amount of money that was trivial to me but going to be significant to her and she had such an intense reaction that I was honestly afraid for her health.

This is both a great honour, and tiring. But I was surprised to find that a lot of Western humanitarian volunteers don’t bother to learn either of the local languages (!!) even if they’ve been there since the start of the war. Whereas I’m visiting longstanding friends who just happen to have had their lives transformed by war, and working with them. What makes me most unusual is existing outside the Westerner bubbles.

I’m not sure if you’re in the situation where a gringo who bothers with Spanish is considered to be unusual, or if immigrants/adult returnees to Argentina tend to be better mannered than that? How things stand in this respect must be a major factor in how people react.

Upon meeting my ex's grandfather (from Waco, TX) for the first time, he asked, "Where ya from son? Ya look kinda dark." Like you, I grew up in Baltimore, but am primarily of English and German heritage. My mortified ex-wife said to him, "He's German, you know, the Master Race!" His reply was even worse. He said, "Well, I guess that's better than that long hair Portugee drug dealer you used to date." He wasn't a drug dealer, he was a musician!